A London implant turns “I can’t move” into “my thoughts click the mouse”

A British medical student loses movement after a diving accident. Life turns into a daily negotiation with gravity, tech, and other people’s hands.

Now he regains a slice of independence through a brain implant from Neuralink, the company tied to Elon Musk. The device reads brain signals linked to intended movement. It then sends those signals to a computer. No hands required. No voice required. Just intent.

In London, doctors place the implant during a long operation at University College London Hospitals (UCLH). The early result looks real. The patient moves a cursor. He opens files and plays chess. He performs all actions with thoughts alone.

What’s Happening & Why This Matters

A BCI implant in U.K. Clinical Trial

The story centres on Sebastian Gomez-Peña, a British medical student who lives with paralysis after a diving accident. Surgeons implant a Neuralink brain-computer interface during a five-hour procedure at UCLH.

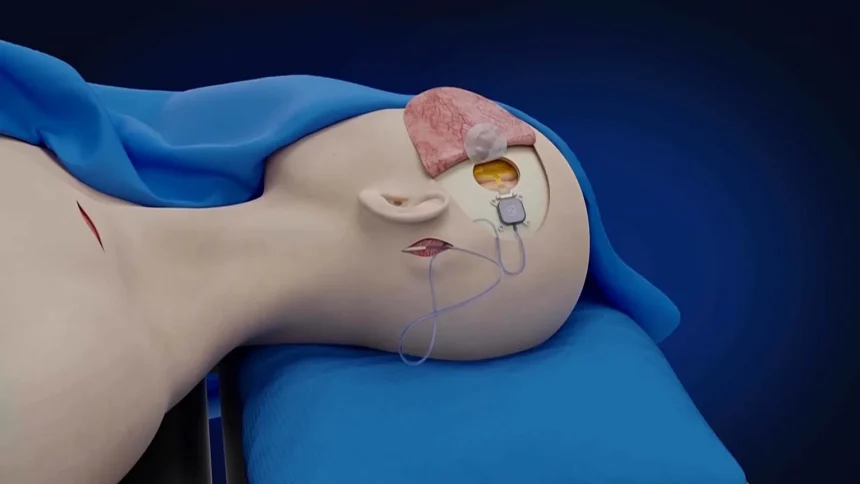

Neuralink designs the system around two main parts.

The first part lives in the brain. A surgical robot places microscopic threads in a specific brain region. Those threads carry electrodes. The electrodes detect tiny electrical patterns from neurons.

The second part lives in the skull opening. A coin-sized chip is flush with the bone. The chip collects the signals. It then transmits them wirelessly to an external computer.

Doctors target the motor cortex. That area helps control voluntary movement. In this case, the team focuses on the brain region linked to hand and finger movement. That design choice makes sense. Cursor control maps well to “hand” intent.

This work is part of an early clinical trial. The trial includes seven participants in the U.K. and 21 participants worldwide, across locations including the US, Canada, and the UAE. That scale stays small on purpose. Early trials hunt for safety signals and basic function. They do not prove long-term outcomes.

Results: Thought-driven Cursor Control Restores Small Freedoms

The practical result looks simple. Sebastian controls a laptop cursor without touching the device. He opens files and plays chess. Both actions sound small… until you imagine life without them.

The system works through pattern matching. Sebastian imagines moving his hand. He imagines moving fingers. The software links those mental “move” signals to a cursor direction. It turns “right” intent into a rightward cursor motion. It turns “click” intent into a click command.

Sebastian describes the change in plain human language. Describing the experience, “It’s a massive, massive change in your life where you can suddenly no longer (use) any of your limbs, and this kind of technology kind of gives you any piece of hope.”

He also explains the mental process in vivid, simple terms. He thinks about moving his hand right or left, or about moving fingers. Then, “the technology just understands what I want to do, and it does it.”

That matters for one big reason. Paralysis steals agency first. It steals a second. A Neuralink brain-computer interface trial in the U.K. targets agency. It provides a direct channel to a computer again. That channel can grow over time.

Today, that channel moves a cursor. Tomorrow, that channel can type faster. It can navigate a phone, control smart home tools, or help with work. It supports learning and social interaction because chat access matters more than people admit.

This is where the future gets spicy. Cursor control acts as the “hello world” of independence. It creates a foundation. It also establishes a training loop. The brain adapts. The software adapts. The person becomes better at driving the system. The system becomes better at reading the person.

Promise Rises, But Research Needs More Time

The medical team calls the technology as a potential turning point for people with severe disabilities. Dr Harith Akram, the U.K. trial lead investigator at UCLH, calls it “a game-changer for patients with severe neurological disability,” and he adds that those patients “have very little to improve their independence.”

The excitement is exciting, and the evidence fuels the innovative drive.

The work is still early-stage. Researchers have not yet published these results in peer-reviewed journals, at least as far as the material provided here is concerned. Regulators do not approve the device for broad use. The trial remains small. The follow-up time remains limited.

So the smart stance looks like this: celebrate the progress, then demand durability.

Long-term safety is vital. The brain does not forgive sloppy engineering. The implant must resist infection risk. The device must resist signal drop-off. The threads must stay stable. The software must keep working across months and years.

Long-term usefulness matters too. Cursor control excites headlines. Daily life demands more. People want reliable text entry. People want to control how they work in bed, in a chair, in noisy rooms, and when fatigued. They want the setup to feel simple, not like a science fair.

This is also a privacy story. A BCI captures neural patterns. That data can reveal intent signals. That data deserves serious safeguards. Medical trials already operate under strict rules. Wider deployment will raise more complicated questions about data handling and user control.

This is why the Neuralink brain-computer interface U.K. trial matters beyond one patient. It tests a full stack: neurosurgery, robotics, embedded hardware, wireless telemetry, AI-driven decoding, and human learning. If that stack holds, it becomes a blueprint.

It also reshapes how society talks about disability tech. We often treat accessibility as a side feature. BCIs force a different framing. They treat access as a primary interface.

TF Summary: What’s Next

The U.K. trial places Neuralink’s implant into real clinical care at UCLH, and then it shows a clear early outcome: Sebastian Gomez-Peña controls a computer cursor with thoughts. He gains absolute independence through a direct brain-to-device channel.

Next steps focus on evidence depth. Researchers extend the follow-up window. They track safety, test reliability, and measure skill gains. They increase trials to learn who benefits most and why.

MY FORECAST: BCIs is a real clinical category, not a sci-fi headline. Hospitals adopt them first for severe paralysis. Consumer hype is real as clinical proof validates the testing.

— Text-to-Speech (TTS) provided by gspeech | TechFyle