Google warns that Australia’s new social media ban for U16 users is nearly impossible to enforce. It might even make children less safe online. The law, which takes effect 10 December, prohibits anyone under 16 from creating or maintaining accounts on YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, Facebook, and X. Violations cost tech platforms up to 50 million Australian dollars (€28 million) per offence. This is one of the world’s harshest penalties for underage online access.

Australia’s internet regulator says the ban protects children from social pressures and harmful content. But Google argues the measure may backfire. The search leader says it limits safety tools and parental features that help kids navigate digital spaces more securely.

What’s Happening & Why This Matters

The World’s Strictest Social Media Age Law

The Australian government positioned its law as a “world-first” child safety initiative designed to reduce exposure to social media’s psychological and behavioural risks. Regulators argue that early access to these platforms exposes children to cyberbullying, body image pressures, and addictive algorithms.

However, Google’s Rachel Lord, senior manager of public policy for Google and YouTube in Australia, told a Senate committee that while the intent is commendable, the execution is flawed.

“The legislation will not only be extremely difficult to enforce, it also does not fulfill its promise of making kids safer online,” Lord said. “The solution to keeping kids safer online is not stopping them from being online.”

Her testimony emphasised a fundamental tension between access control and safety control. When children can’t create accounts, she explained, they lose customised protections. Features like restricted mode, ad filters, and content recommendations are built specifically for young audiences.

Unintended Consequences: Less Safety, Not More

According to Lord, cutting off under-16s from official accounts would force many children to browse anonymously. This would bypass the very protections the law intends to create.

For example, on YouTube, signed-in users under 13 automatically access YouTube Kids, a heavily filtered environment. Those aged 13–15 use parent-supervised accounts, allowing guardians to control what children can watch and track their activity. Under the new law, both options could vanish for users in Australia.

Without these systems, children might instead access standard YouTube as unregistered users, stripping away important guardrails. That means exposure to algorithmic recommendations promoting unhealthy body standards, harmful challenges, or explicit content.

Lord cited YouTube’s autoplay restrictions and ad-free experience for minors as key safety layers that depend on logged-in accounts. Removing those accounts, she said, removes the ability to apply those protections.

Industry and Government Standoff

The law, initially passed in 2024, excluded YouTube before Australia’s internet safety regulator recommended its inclusion earlier this year. Since then, tech companies have questioned how regulators plan to verify users’ ages, enforce penalties, and handle parental consent.

Experts say age verification is technically challenging and privacy-sensitive. Requiring identity checks or biometric data could expose users — including minors — to new risks of data breaches or surveillance abuse.

Media outlets in Australia have speculated that Google could challenge the law in court, though Lord declined to confirm any legal action. For now, the company says it remains committed to collaborating with the government on a more balanced digital safety framework.

TF Summary: What’s Next

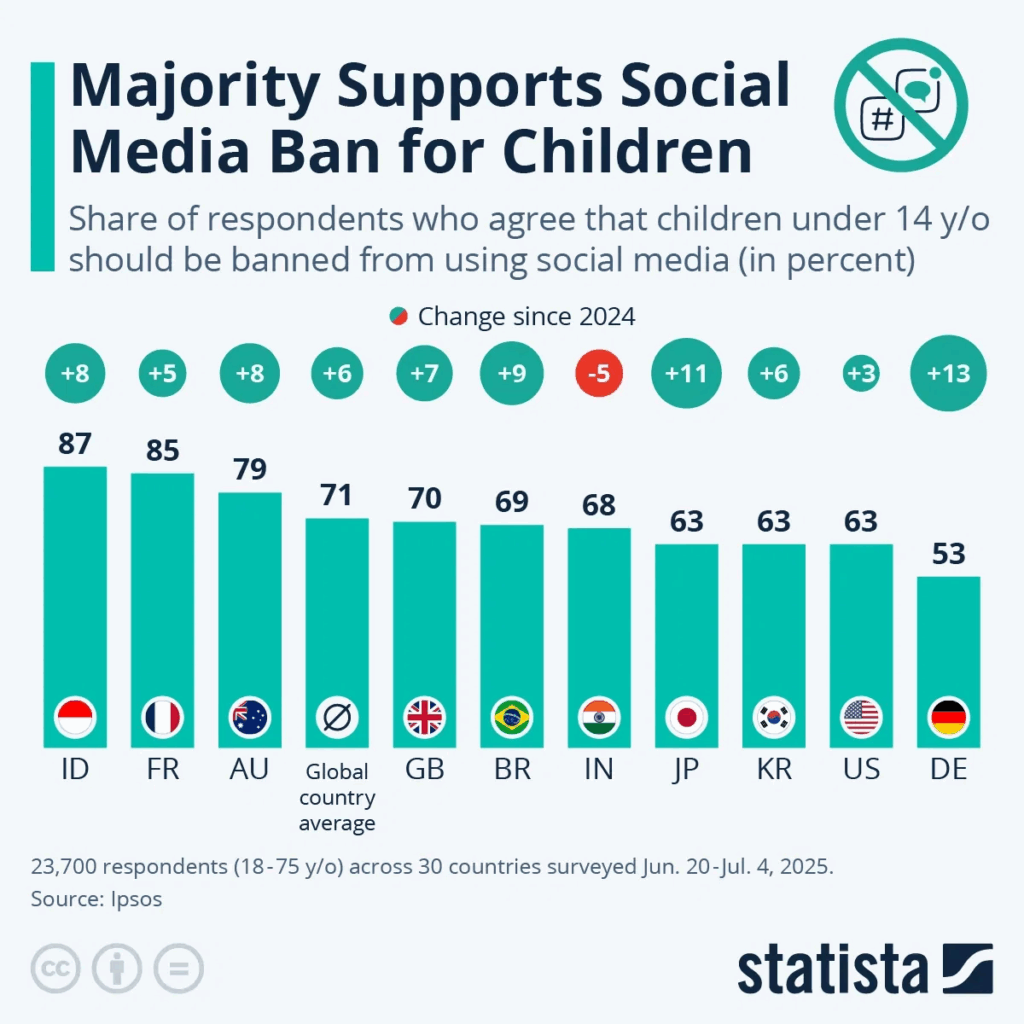

Australia’s U16 social media ban is a new global standard. But it is also kicking off a fierce fight about how far regulation can (and should) go. While the intent to protect children is widely supported, the practical enforcement and technical feasibility is deeply contested.

MY FORECAST: As the December rollout draws near, the law is a test case. The test: whether governments meaningfully police age-based internet restrictions without weakening the safety tools designed to protect young users. Other countries are watching — from the U.S. to Europe — and may soon follow Australia’s lead

— Text-to-Speech (TTS) provided by gspeech