Glass Data Storage: Microsoft Project Silica Slabs

Data used to be carved in stone. Then we invented tape, disks, and clouds — each more convenient, each more fragile in its own way. Researchers are circling back to something ancient and oddly poetic: glass. Microsoft is testing a storage technology that burns information into quartz slabs designed to survive thousands of years. Yes, thousands. Not “until the next software update breaks compatibility,” but “longer than most civilizations.”

The project, known as Project Silica, explores whether glass can store massive amounts of data with zero power draw and near-mythic durability. In a world drowning in digital exhaust — photos, logs, models, backups — long-term storage is becoming less of a technical curiosity and more of a survival strategy for knowledge itself.

What’s Happening & Why This Matters

Ancient Material, Futuristic Purpose

Microsoft researchers demonstrate that carefully engineered glass can serve as a stable, ultra-dense archive medium. Unlike magnetic tapes or solid-state drives, glass does not corrode, demagnetize, or slowly forget your files while you sleep. Properly made silica glass resists heat, moisture, electromagnetic noise, and time’s slow gnawing teeth.

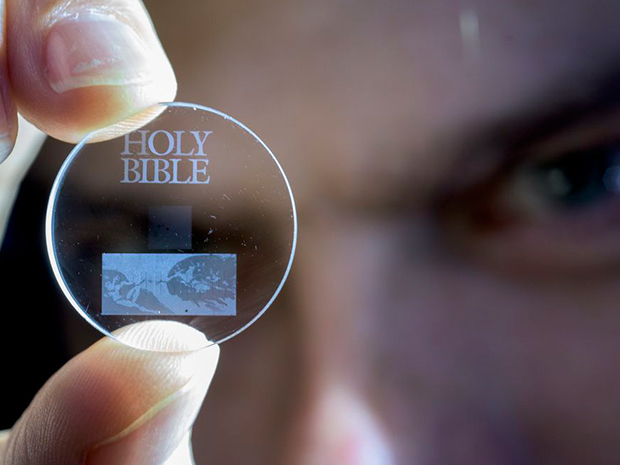

According to research published in Nature, the team stores data within the glass’s volume rather than on its surface. They use ultrafast lasers to carve microscopic structures — tiny 3-D features that encode bits of information. These structures sit safely beneath the surface, immune to scratches and environmental abuse.

The payoff is staggering durability. Properly stored glass could last for millennia. No power needed or maintenance cycles. No spinning platters begging for electricity like caffeinated hamsters.

Researchers describe the medium as “thermally and chemically stable” and resistant to environmental stress. In practical terms, that means your data survives fires, floods, and electromagnetic chaos far better than traditional storage.

How the Writing Process Works

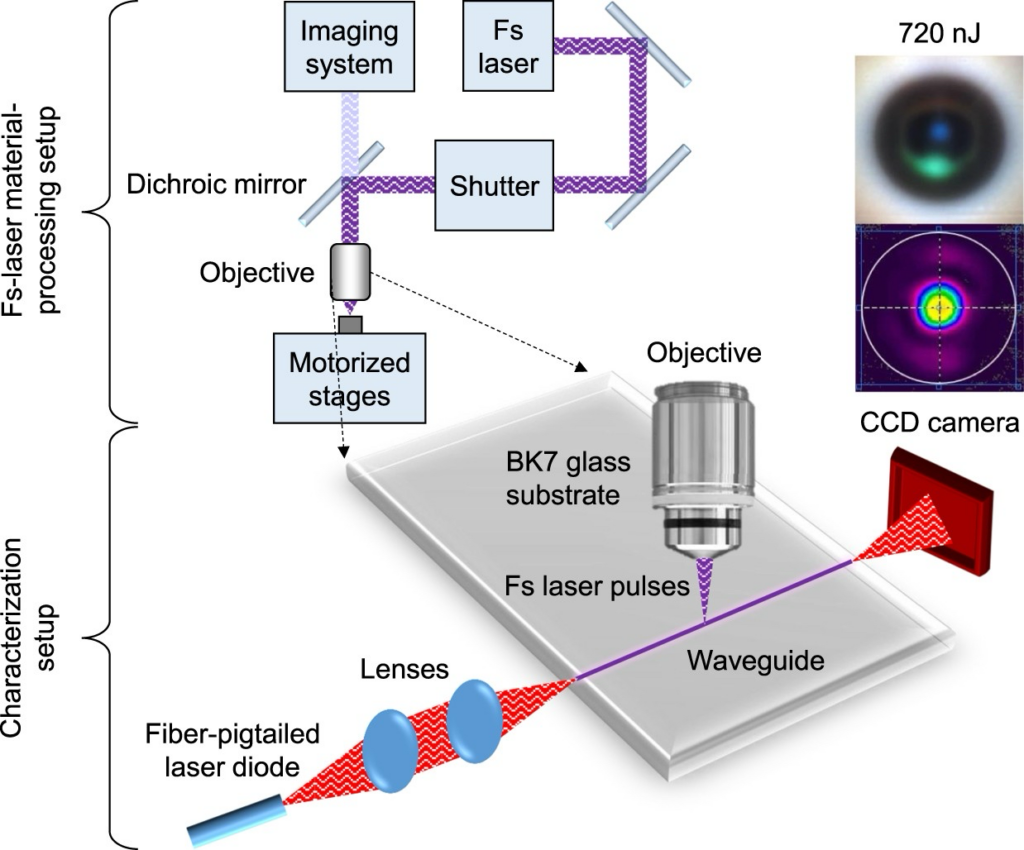

The writing mechanism feels like science fiction with lab coats. Ultrafast femtosecond lasers fire pulses so brief they occur on timescales almost too small to imagine. Each pulse alters the internal structure of the glass at microscopic points, creating voxels — three-dimensional pixels of stored information.

The process is not simple engraving. It is a controlled structural transformation inside the material. Think of it as rearranging the glass at a molecular level rather than scratching the surface.

Femtosecond lasers enable extremely fine resolution and high data density. The system reportedly achieves densities exceeding one gigabit per cubic millimeter.

That density matters. Archival storage must pack enormous volumes into manageable physical space. Museums, governments, and scientific institutions generate data measured not in gigabytes but in petabytes and beyond.

Writing data into glass is slower than writing to conventional drives. However, archival storage values permanence over speed. Nobody expects to back up a live database to quartz in real time. This is deep-time storage — digital amber for future archaeologists.

Reading the Data Back

Storing information for ten millennia is useless if no one can read it. Microsoft addresses this by using optical systems to scan the microscopic features embedded in the glass. Cameras and imaging software interpret the patterns and reconstruct the stored data.

Because the information lives in three dimensions, the reading system captures depth as well as position. Machine-learning tools help efficiently decode the structures. In principle, future technologies could still interpret the data even if current hardware disappears.

The future-proofing is not accidental. One of the biggest risks to long-term storage is technological obsolescence. Ask anyone who has tried to read a floppy disk recently.

Why the World Needs Deep Archival Storage

Humanity produces data faster than we can responsibly preserve it. Scientific observations, legal records, cultural works, genomic databases, and climate models all demand long lifespans. Traditional storage systems degrade within decades at best.

Tape libraries, currently the backbone of archival storage, require periodic rewriting and controlled environments. Solid-state drives lose charge over time. Hard disks fail mechanically. Cloud storage is just someone else’s hardware problem — until it isn’t.

Glass storage offers a radical alternative: write once, store safely, ignore for centuries.

Potential users include:

- National archives preserving historical records

- Space agencies storing mission data

- Media companies safeguarding cultural catalogs

- Scientific institutions maintaining long-term research datasets

Microsoft has already demonstrated real-world tests, including archiving cultural content on glass slabs. The appeal is obvious. Knowledge is less fragile than the institutions that created it.

Energy and Environmental Implications

Traditional data centers consume enormous electricity even when idle. Cooling alone rivals the energy use of small cities. Long-term cold storage still requires controlled environments.

Glass storage consumes no energy once written. It just sits there like a smug, silent librarian who never sleeps.

As AI models, surveillance systems, and digital economies generate oceans of data, energy-neutral storage are essential. Otherwise, we risk building a civilization powered mostly by the need to remember itself.

Limitations and Open Questions

Despite the promise, the technology is not ready to replace conventional storage. Writing speeds remain slow. Retrieval requires specialized equipment. Costs are high. Standardization does not yet exist.

Another subtle problem lurks in the future: context loss. Storing bits is easy; preserving meaning is harder. A file that is perfectly encoded means nothing if future readers lack the software, language, or cultural framework to interpret it.

Some archivists advocate storing human-readable instructions alongside digital data — essentially a Rosetta Stone for the information age.

Glass storage solves durability. It does not solve the interpretation. That challenge is deliciously human.

TF Summary: What’s Next

Microsoft’s glass storage research signals a quiet but profound shift. Data preservation is no longer just an IT concern. It is becoming a civilizational one. As digital memory replaces physical records, humanity needs media that can outlast political cycles, corporate lifespans, and technological fashions.

Project Silica does not replace everyday storage. It complements it. Think of it as the Library of Alexandria redesigned to survive fires, wars, and centuries of neglect. If development continues, glass archives could safeguard humanity’s scientific and cultural memory far into the future.

MY FORECAST: In a universe where entropy always wins eventually, building something meant to resist it for 10,000 years feels almost rebellious. The species that once scratched stories onto cave walls burns them into crystal. Same impulse. Better materials.

— Text-to-Speech (TTS) provided by gspeech | TechFyle